Interesting things appear in the Inbox now and then, and this was one of the more interesting ones. Jeffrey Krause’s dad, Darrel W. Krause, was one of the first people American Kawasaki hired when it came to America, at just about the same time the Mach III 500 made Kawasaki a large blip on our radar screen.

Jeffrey writes:

Hello Mr. Burns,

I am the son of one of the Kawasaki-USA (KMC/AKMC) founders.

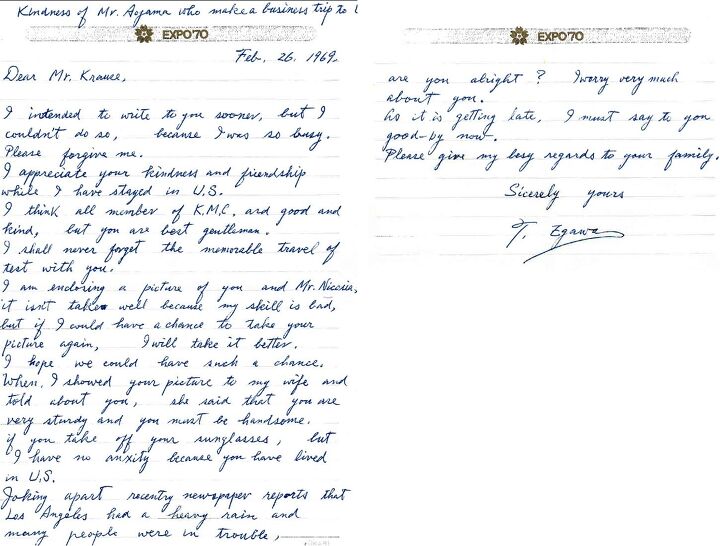

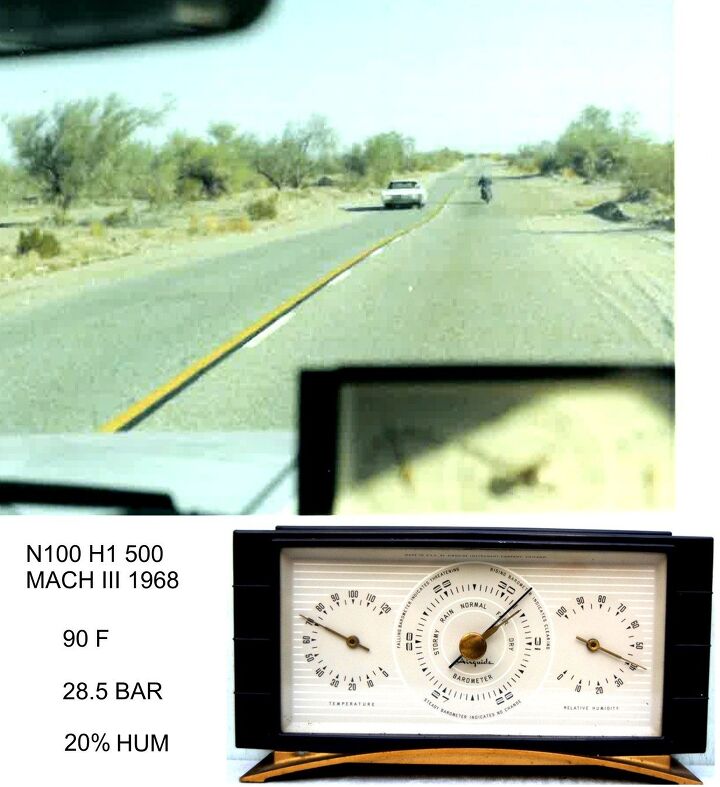

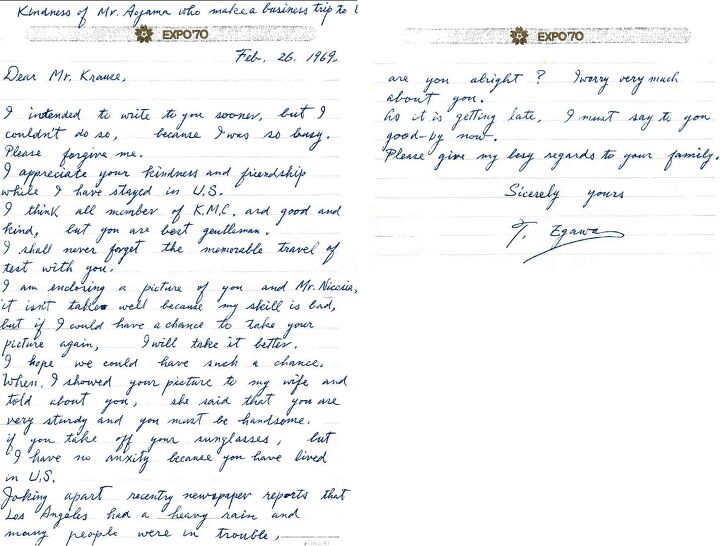

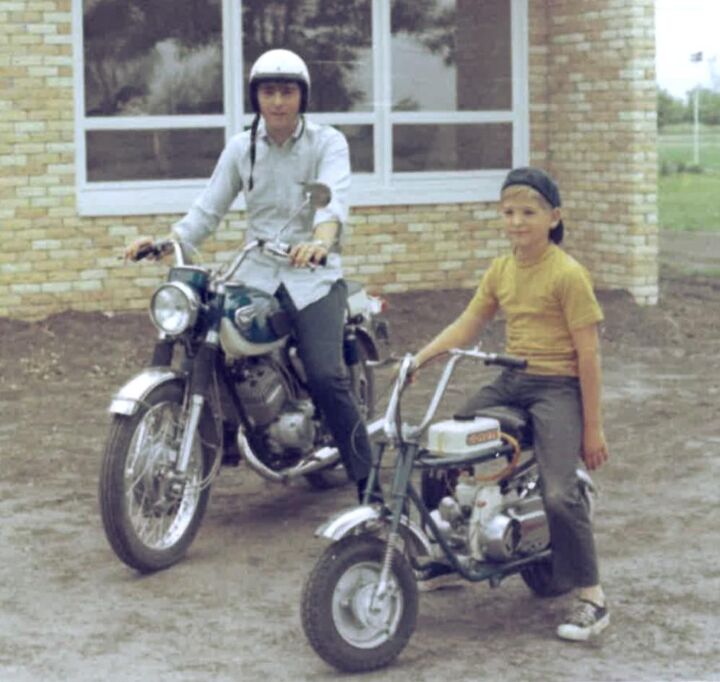

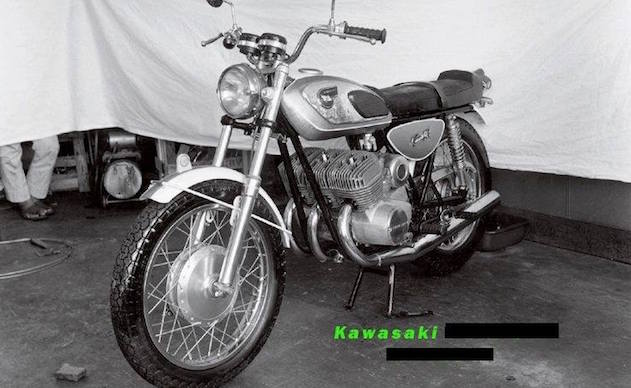

I wrote a few articles regarding the US history of Kawasaki. Recently, I found additional photos, documents and a thank-you letter for my father. These newly-surfaced documents (all in one stash) are Darrel’s records about the testing of the prototype N100 from Japan in 1968. It was the first Kawasaki 2-stroke Triple, which would become known to the public as the 1969 H1-500 / Mach III.

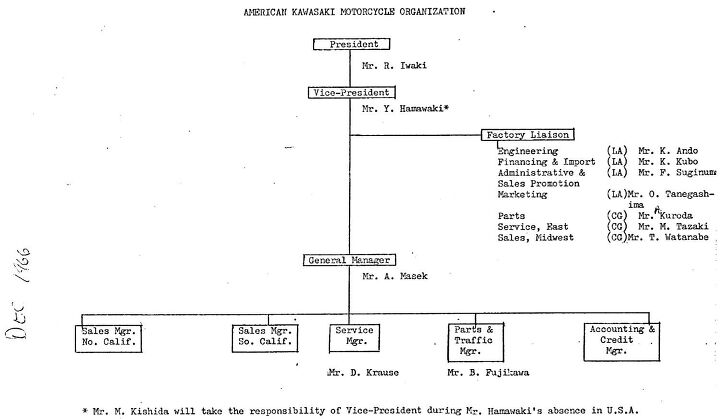

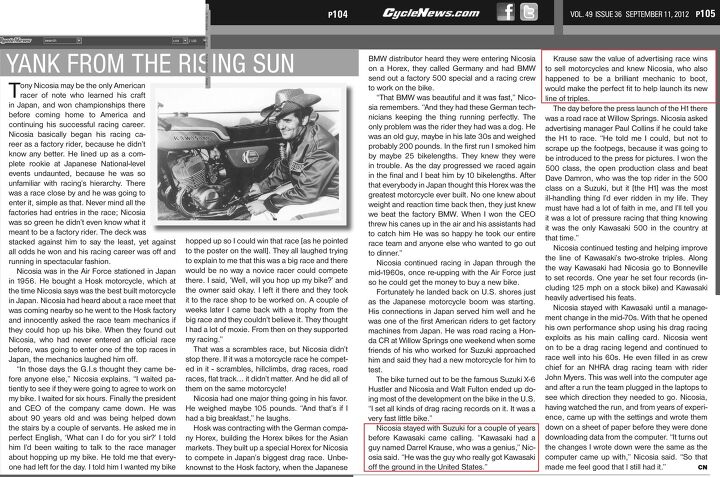

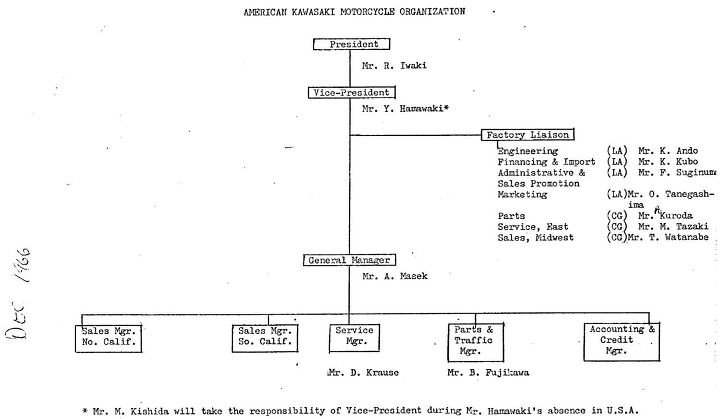

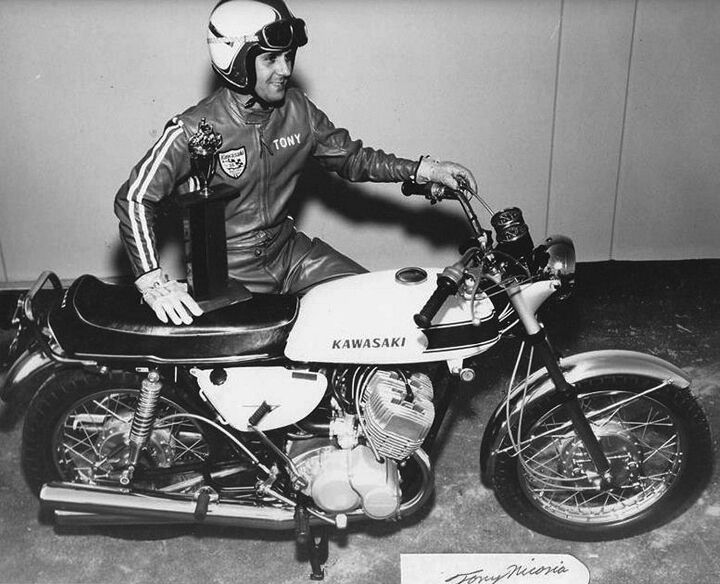

Darrel was (as far as I can tell from research) only the second ‘native’ manager hired by Kawasaki when they established a corporate presence beginning in 1966. Darrel, in turn, later hired Tony Nicosia.

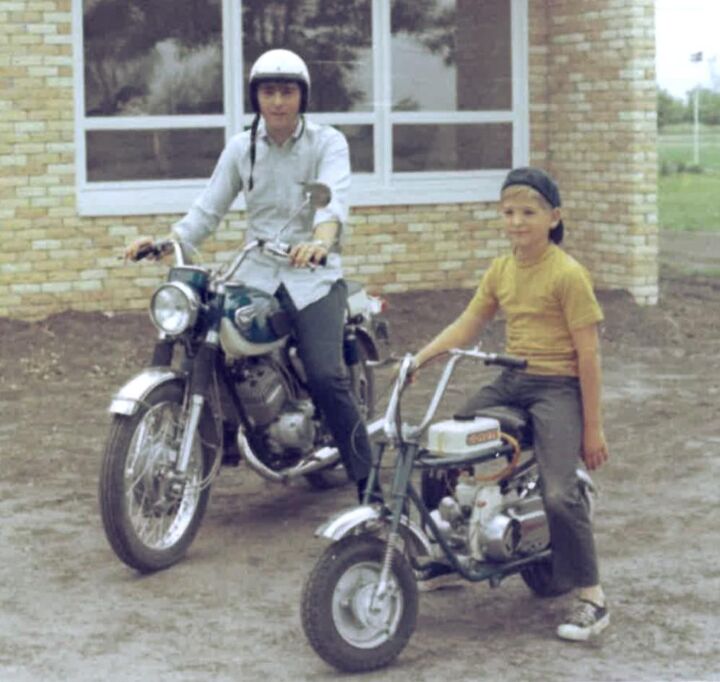

My dad, who was 27, was hired after sacrificing his own job as manager of a brand-new dealership, to prevent Kawasaki from being defrauded by that dealership’s owner, who’d hired him. We were instantly homeless and jobless, and fled the state in fear of retribution from the owner.

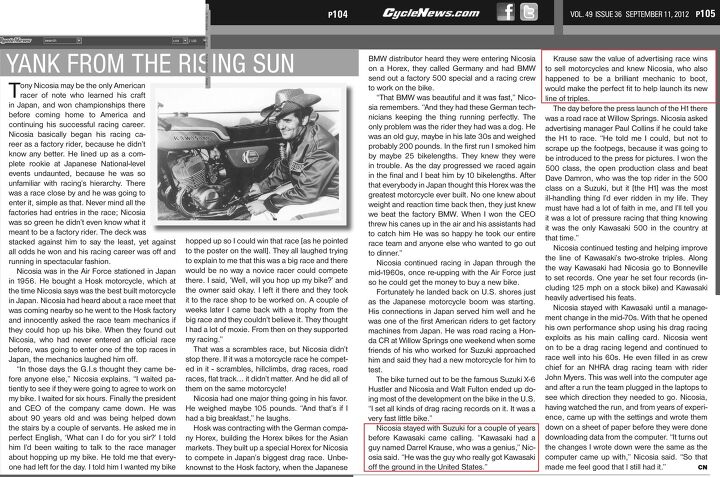

I have many original slides, negatives and even a video or two. Darrel’s pre-Kawasaki career was managing his own photography studio in South Dakota, so he wound up also serving as KMC/AKMC’s first resident photographer. Because of this he was only rarely seen in early photos – wrong side of the camera :).

It would simply be nice if people could have a chance to see these photos and some of the key elements of my dad’s story, which is 100% true.

Yours,

Jeff Krause

How could MO turn down an offer like that, especially since Jeff had already written the thing up. In second person. Why not? Take it away, Jeff.

It’s 1966. You are 27 years old. You had temporarily dropped out of college to pursue an offer to help manage a new motorcycle dealership. You moved your young family from South Dakota to Omaha for this, but the dealership shuts down almost before it starts, due to shady legal dealings.

What now? You are basically homeless, with a wife and two small children depending on you to figure this out. However, someone notices you and your struggle, and is impressed enough to make you a job offer in the wake of this disaster. You sign on with an obscure Japanese company none of your friends have ever heard of. They’re trying to sell motorcycles for as low as $131 wholesale. In 1966, they have basically zero market share in the US. Their total budget for the year, for the US, is initially not very much. But if progress is shown, you’re told, the parent company may invest more.

The mother company in Japan is about as desperate as a multinational corporation can be when it comes to its motorcycle division. Compared to their other divisions – ships, factory machinery, engines, aircraft and rail – the motorcycle division is not exactly a moneymaker.

The Japanese government expects more motorcycles and spares for some years to come. Government pressure was a very real thing in Japan, so quitting would have consequences. The company must either withdraw from the motorcycle business, or go all-in by founding a corporate presence in the West specifically for motorcycle sales. Stuck between profitability and the government, the company decided to make the most of a bad situation by trying to expand sales. Before 1966, Kawasaki sold tiny quantities of bikes in the US under the Meguro name.

Since the ‘big’ Japanese players – Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki – had already established beachheads in America, extracting market share was not going to be easy. The others all had a head-start. On the other hand, those brands were also leading interference for the Japanese team, in a game that was heretofore played really only by the British and Americans.

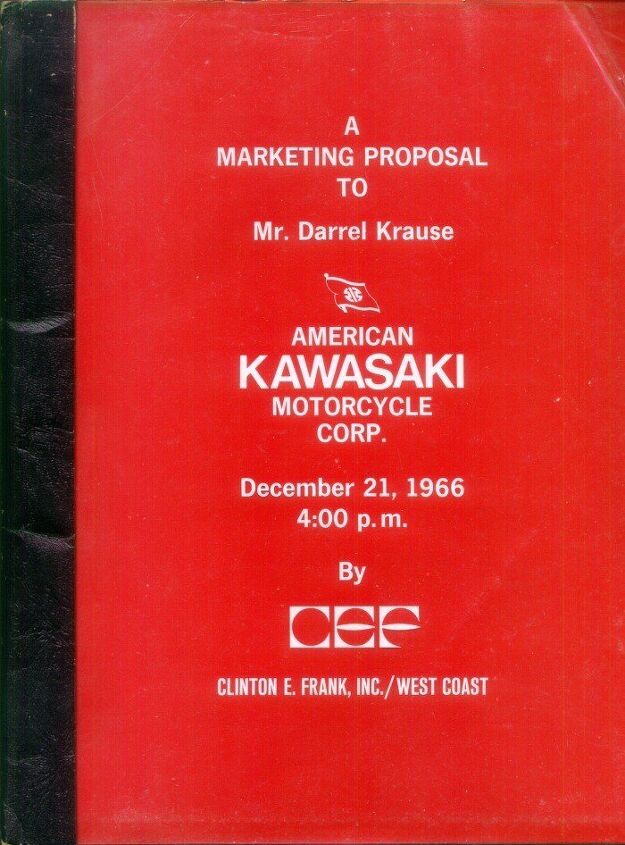

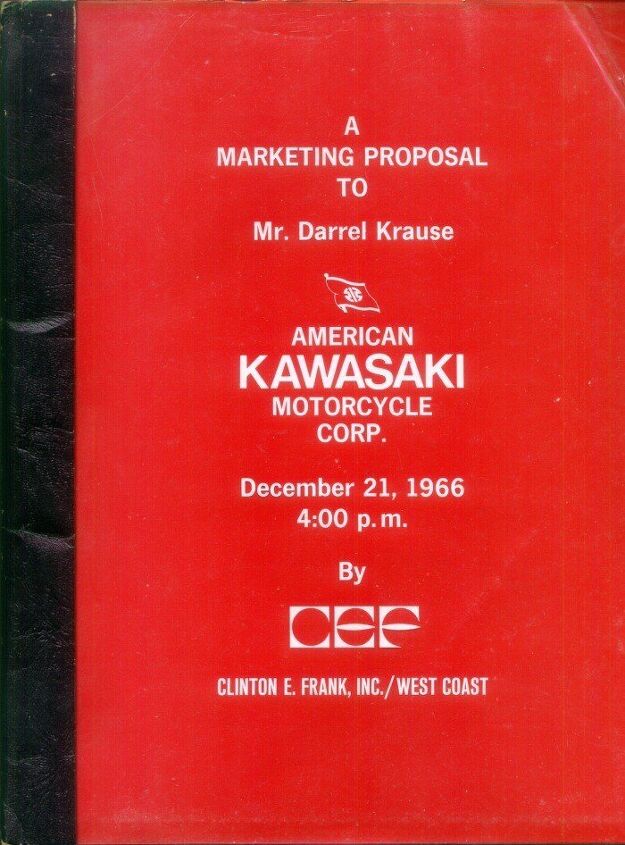

Independent importers like Alan Masek of Masek Auto Supply in Nebraska were interested (Alan is probably the guy who offered you the job; his father Fred was already Kawasaki’s midwestern distributor). Ryozo Iwaki and Yoji Hamawaki got approval from the home office in Tokyo to spend a little money on the venture. At first, they hired just a couple of ‘natives’ like Alan and you, dad, Darrel Krause. They referred to this little company by the acronym AKMC, and hired marketing consultant Paul Collins. Having fled Omaha after having to call the cops on your own boss at that failed dealership, you move to Chicago for the new job, where you’re immediately tasked with investigating a marketing proposal on Kawasaki’s behalf.

You dive in headfirst. The import competition: Honda’s models are very reliable, and their sensible and politically-correct slogan is ahead of its time: “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda”. Nancy Sinatra sings “These Boots are Made for Walking” on the radio. Meanwhile Yamaha and Suzuki chase Honda for market share in the West. Your Brand? Not much of a player. What to do? Get attention. How? Ask the factory in Japan, who’ve been making those little $131 motorcycles, to produce something more powerful, yet inexpensive. Something to grab attention. Ideally the motorcycle equivalent of a cheap American muscle car.

You dive in headfirst. The import competition: Honda’s models are very reliable, and their sensible and politically-correct slogan is ahead of its time: “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda”. Nancy Sinatra sings “These Boots are Made for Walking” on the radio. Meanwhile Yamaha and Suzuki chase Honda for market share in the West. Your Brand? Not much of a player. What to do? Get attention. How? Ask the factory in Japan, who’ve been making those little $131 motorcycles, to produce something more powerful, yet inexpensive. Something to grab attention. Ideally the motorcycle equivalent of a cheap American muscle car.

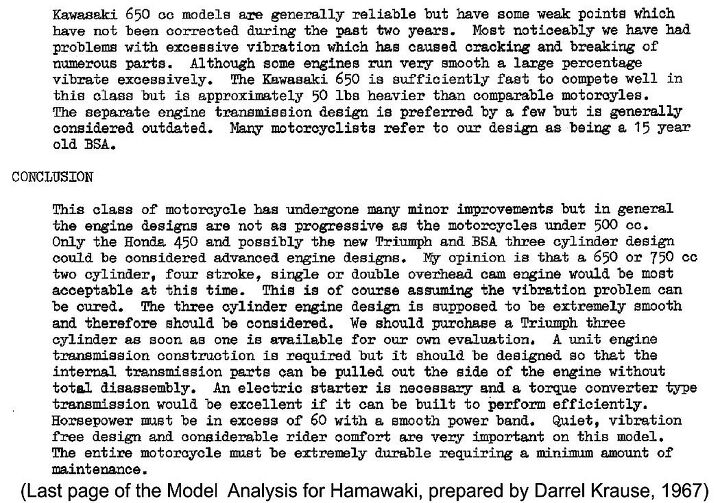

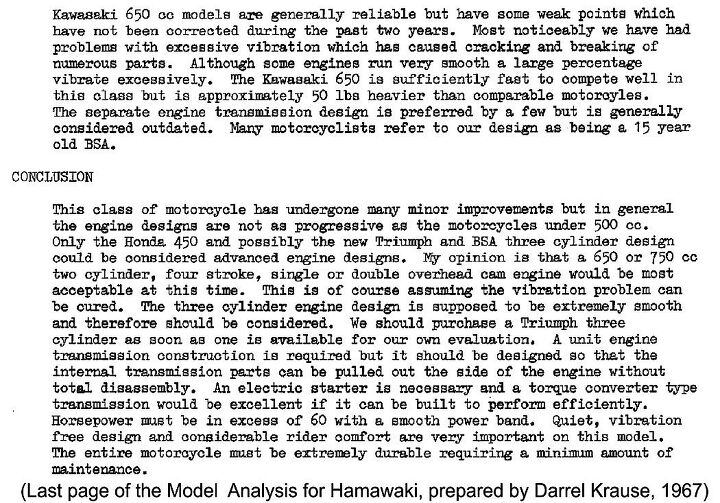

This is a motorcycle few would buy for use inside of Japan. But you do have an edge, because your factory has aircraft engineers it can borrow from that division – and some pretty good ones too. So you write up a “Big Bike” comparison and analysis.

This 1967 wish list contributes both to the development of a three-cylinder motorcycle and a big-bore four-stroke. For now, you are unaware the factory has either already started working on both, or soon will. Your report to your superiors helps confirm their priorities.

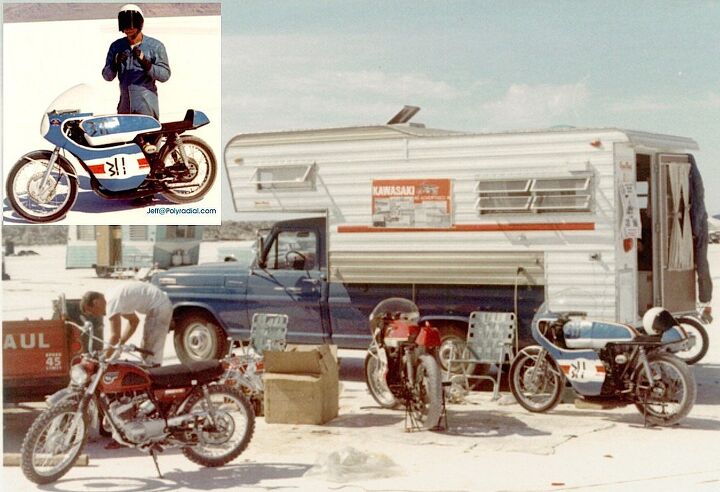

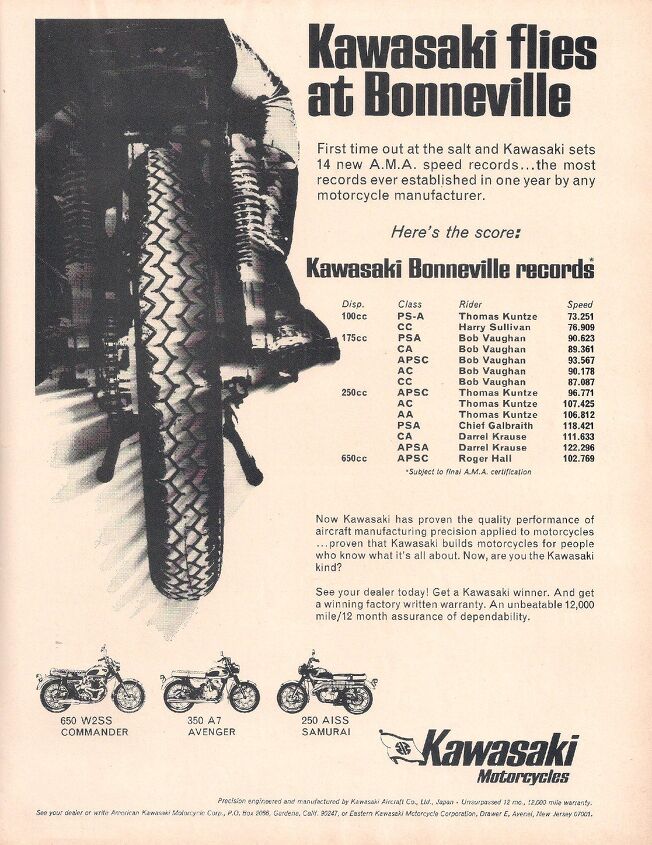

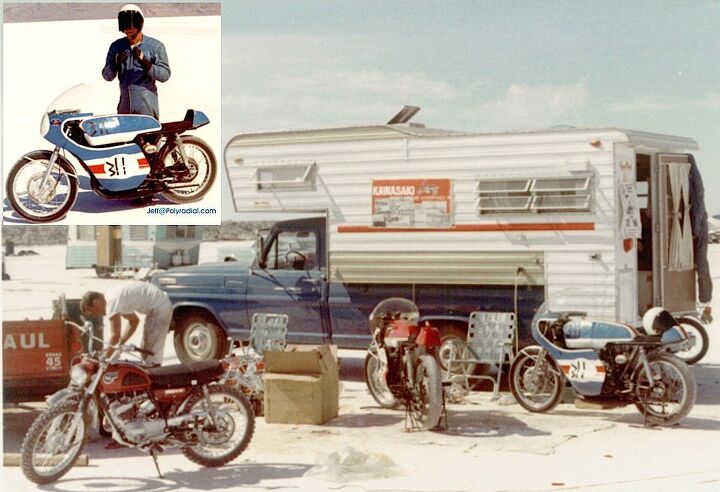

A hands-on kind of a guy, Darrel, along with Chief Galbraith and others, set a bunch of Bonneville records on Kawasakis before the Mach III even existed.

It took about one Chicago winter for everyone to agree establishing a new HQ in Gardena, California, might be a better idea. Honda was there already, while Suzuki and Yamaha were also putting down roots in Southern California. You pick up the family, including me and my sister, and move to Long Beach.

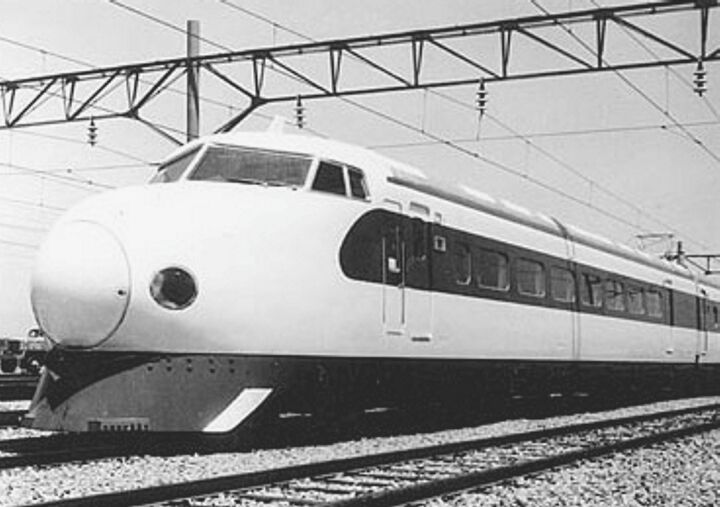

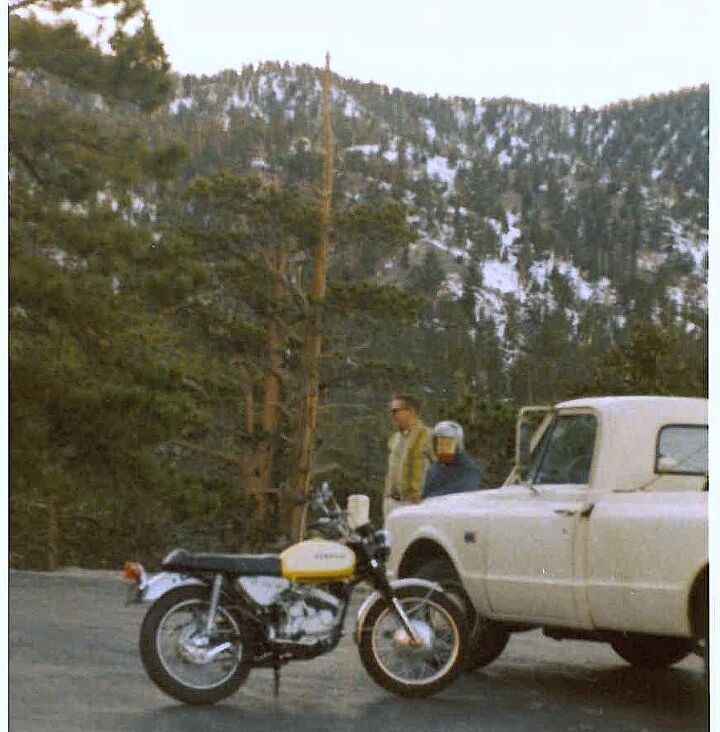

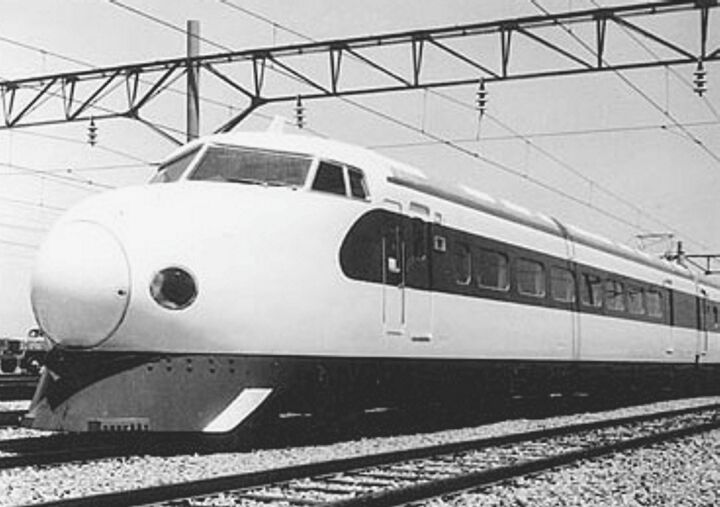

Not long after your report lands, what does the factory send over for testing? A prototype designated N100 – a 500 cc piston-ported two-stroke with three Cylinders, three exhaust pipes, three carburetors and CDI Ignition (a first).

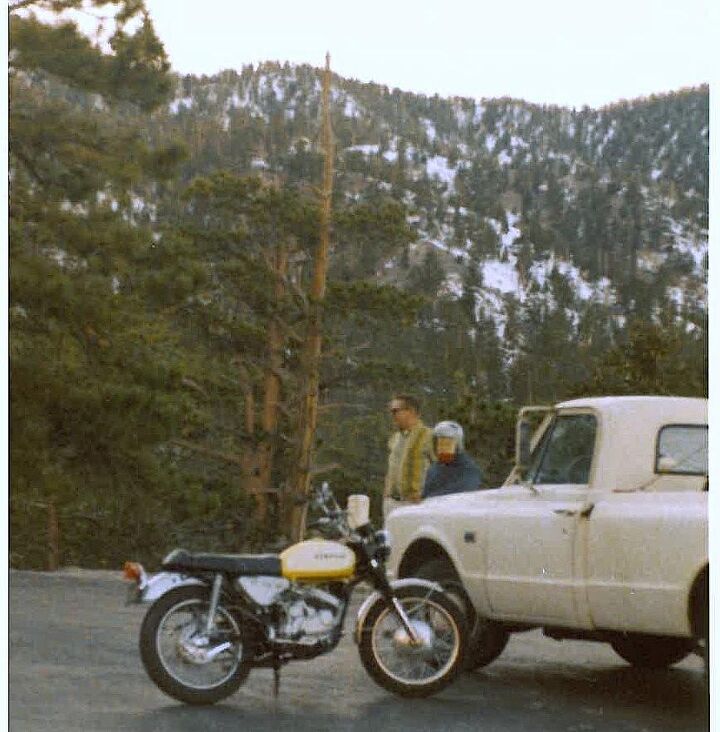

N100 prototype, trying hard to look British before somebody in the styling department had a better, more contemporary idea that managed to penetrate.

It wasn’t exactly what you had in mind, but it was fast, decent-handling (for the era) and way less expensive than anything any other brand was offering with such big-bike performance.

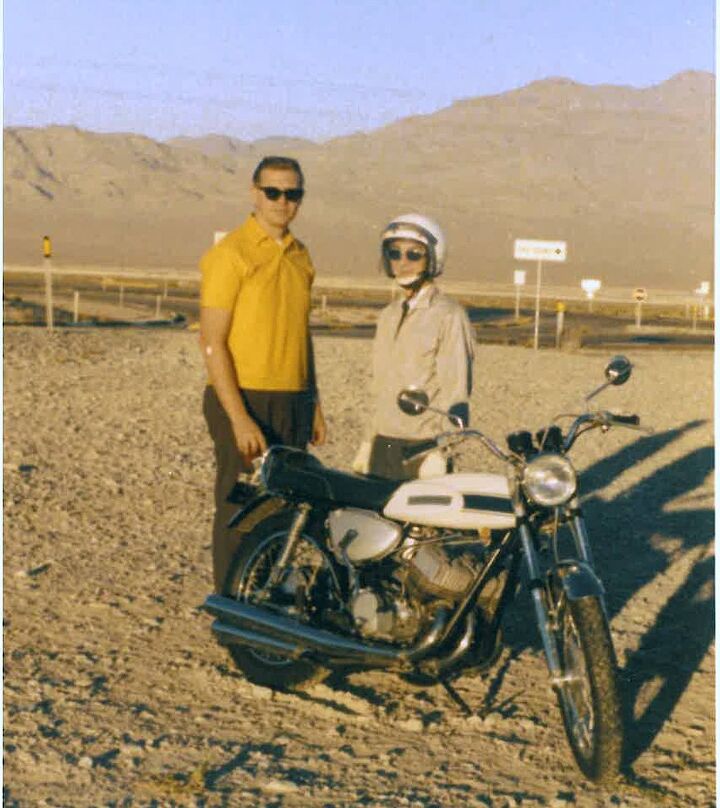

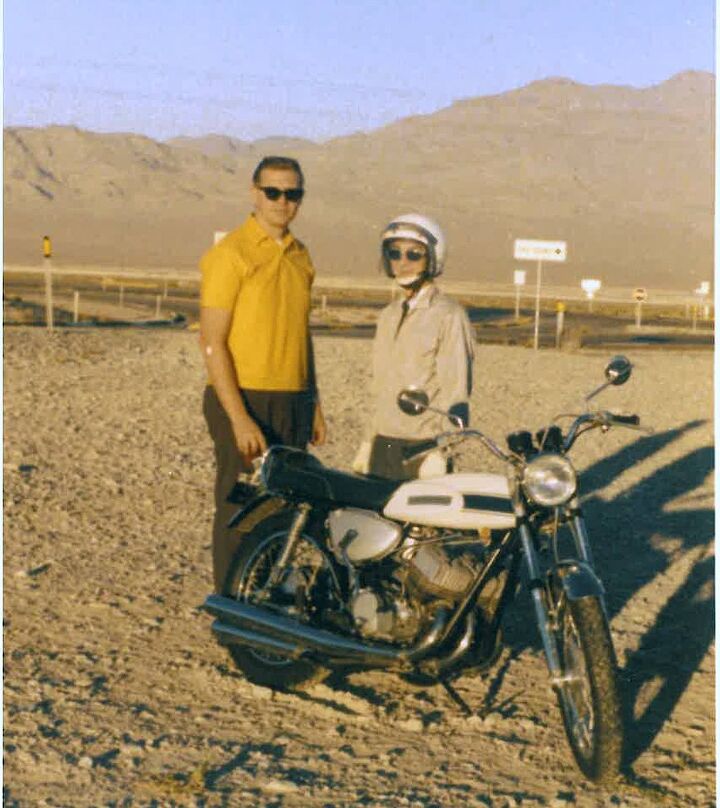

You wear simultaneous hats including AKMC’s first Service Manager, New Products Manager, and also its first Racing Manager. Your main title requires you to test this strange new beast on challenging roads and extreme conditions within the target market country.

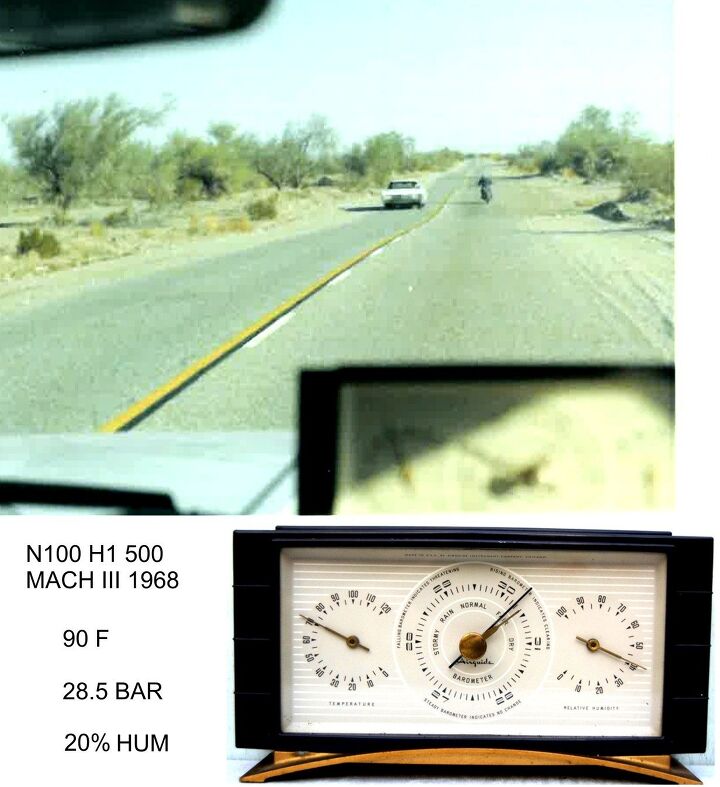

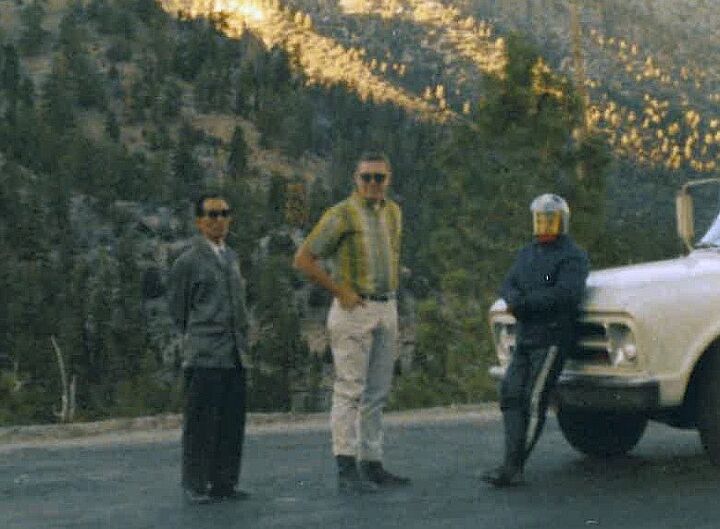

OK, fire up the pickup truck, load up an advance sample of next year’s A7-350 Avenger as a chase bike, gas up the prototype, and prop a home weather station on the dash of the pickup for some metrics. You head east, where there are still no speed limits in 1968. Your test rider and engineer can run the bike though its paces in the heat of the desert and also the freezing air of the mountains not far away: Yuma. Needles. Mexicali.

You test two slightly different engines. Make notes. Forward to the factory through a gracious engineer named T. Egawa, who was along to facilitate testing. It was a team: The knowledge and skill of a professional racer as a test rider, A skilled engineer from the factory in Japan, managers to budget, report (and pay everyone) – and the amazing talent of Kawasaki’s aircraft engineers in Japan, tasked with a huge workload to bring such a motorcycle to fruition in such a short space of time.

Less than a year after this shoe-string effort, Cycle World dubs the Mach III “World’s Fastest Production Motorcycle” – ‘Fastest’ in this case meaning a combination of quick and fast. But that’s just one of a slew of awards from the media as the accolades begin rolling in. Suddenly Kawasaki is a player in the US market.

There was also something inexplicably awesome about the sound of a two-stroke Triple. Customers at the dealerships noticed it, and in 1972 the H1 was joined by the even more outrageous H2 Mach IV 750. Suzuki flattered Kawasaki’s engineers with the GT750 Triple three years later, partially perhaps to cash-in on that super-cool Triple sound.

Inexpensive? Yes. Though it was perhaps the most expensive bike Kawasaki had produced up to that time, the H1 was still much cheaper than a Honda CB750 or anything else, none of which could quite match its smoking banshee two-stroke performance in a straight line, a fact which did not go unnoticed at the height of the muscle car era.

This unapologetic, no-frills 1/4-mile king put a no-name brand on the global map in just a matter of months through the skills of Vice President Alan Masek, Marketing/Promotional Manager Paul Collins, and another guy you hired named Tony Nicosia, who went on to make quite a name for himself after babysitting for your kids a time or two.

The long and short of it is that the 1969 H1 started a snowball of models that set the stage for the release of the first motorcycle to really earn the title Superbike, the 1972 Z1, and I’m super proud you were involved in all of it.

Is there a lesson to be learned? I think there is: If you already have a brand reputation to protect, there are always plenty of people around to hold you back. But if you don’t, bold moves might be just the thing.

Darrel Krause, who had quite the life and his share of bold moves according to his obituary, died in 2003, in Santa Maria, California.

Become a Motorcycle.com insider. Get the latest motorcycle news first by subscribing to our newsletter here.

The post Kawasaki Comes to America, Jeff Krause’s Dad, and the ’69 H1 Mach III appeared first on Motorcycle.com.

【Top 10 Malaysia & Singapore Most Beautiful Girls】Have you follow?